Throughout the centuries, the crucifixion of Jesus Christ has been portrayed by artists, storytellers and musicians. An agonizing journey beneath the crushing weight of the wooden cross. Yet, a closer reading of the Gospel accounts offers a more nuanced picture—one that distinguishes between artistic tradition and historical detail.

Understanding when Simon of Cyrene entered the scene helps us grasp both the physical reality of the event and its profound spiritual meaning.

The cross Christ bore was the weight of a fallen world. We will see in this article that Simon of Cyrene carried the timber, but only the Son of God could bear the guilt and grief of humanity. What began as a sentence of death ended as a triumph of life. To understand what truly happened on the road to Golgotha, we must turn directly to the inspired record. Each Gospel writer was moved by the Spirit to record precise details, and when read together, they reveal a consistent truth.

“Then they spat in His face and beat Him; and others struck Him with the palms of their hands, saying, ‘Prophesy to us, Christ! Who is the one who struck You?’” Matthew 26:57–68

Most of us are familiar with the traditional account of Jesus’s crucifixion: After appearing before the Sanhedrin and being beaten and spat upon, Jesus was taken before Pontius Pilate.

“Then they led Jesus from Caiaphas to the Praetorium, and it was early morning. But they themselves did not go into the Praetorium, lest they should be defiled, but that they might eat the Passover.” John 18:28–31

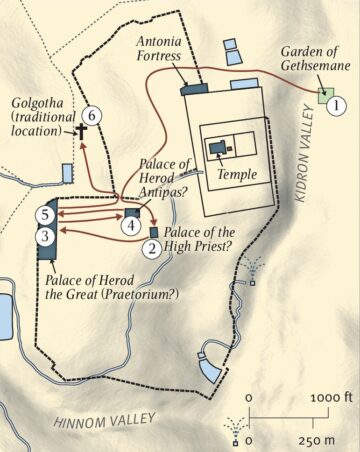

Who led Jesus to the Praetorium, and what was the Praetorium? Early the next morning, these same Jewish authorities — the priests, elders, and members of the Sanhedrin — brought Jesus to the Praetorium (the Roman governor’s headquarters, likely Herod’s Palace in Jerusalem) to face Pontius Pilate.

The Praetorium (Greek: πραιτώριον, Latin: praetorium)

The praetorium was the official residence or headquarters of a Roman governor (in this case, Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem).

During the major Jewish feasts, Pilate normally stayed in Herod’s Palace on the western side of the city rather than at his usual base in Caesarea Maritima. Caesarea Maritima is located on the coast and would have required days of travel back and forth.

Therefore, when the Gospels say Jesus was taken to “the Praetorium,” it means Pilate’s official judgment hall inside Herod’s Palace in Jerusalem.

The Sadducees and Pharisees didn’t have any reservations in watching Jesus be tortured on the cross at Golgotha; ironically, they didn’t wish to be defiled for Passover by seeing him beaten by the Roman soldiers, and yet they unlawfully struck him themselves.

When we read the Gospels closely, there are at least two distinct occasions when Jesus was physically beaten under Roman or Sanhedrin authority — one before his formal sentencing by Pilate, and one after the sentence was given. After sentencing, he was scourged by a company of soldiers, humiliated and beaten beyond what we can imagine. Then he was led from the praetorium and forced to carry a heavy wooden cross (as history records) up the road to Calvary (Golgotha).

However, that is not what the scriptures say happened. John’s record of this event would seem to indicate that Jesus carried the cross all the way through the streets and up to Golgotha. And yet, the other three gospel records agree that Jesus never carried the cross at all. Or, if he did try to carry it, the soldiers compelled a man named Simon of Cyrene to take it from him and bear it the entire way. Is there an error? No. We read in the gospel of John that Jesus…

“Then he (Pilot) delivered him to them to be crucified. So they took Jesus and led him away. And he, bearing his cross, went out to a place called the Place of the Skull, which is called in Hebrew, Golgotha.”

We must take a moment to clarify one important point before we proceed to examine the harmony within these records and understand why it appears that John has a different reckoning.

Golgotha — The Original Term

- The Gospels use the Aramaic word “Golgotha” (Γολγοθᾶ in Greek). Meaning: “Place of the Skull.”

- Location: Just outside the walls of Jerusalem, near a main road where Roman executions were visible to passersby (John 19:20).

- It’s where Jesus was crucified. (Even now, there is no agreed-upon location for where Golgotha/Calvary was located.)

Calvary — The Latin Translation of “Golgotha”

- When the Bible was translated into Latin (the Vulgate), the word “Golgotha” was rendered as “Calvaria.”

- Calvaria in Latin also means “skull.”

- From that word, English inherited the word “Calvary.”

So, Calvary and Golgotha are the same place. “Calvary” is simply the Latin-derived name, while “Golgotha” is the Aramaic/Hebrew name.

Why This Matters

- The original Gospel writers were describing the same location from different linguistic perspectives.

- In English Bibles:

- Matthew, Mark, and John use “Golgotha.”

- Luke (in the KJV) says “the place which is called Calvary” (Luke 23:33).

- Modern translations sometimes keep “Golgotha” in all four for clarity.

To be clear, when Christians say “the cross of Calvary”, they are referring to the crucifixion at Golgotha — the same hill, the same event, just through a Latinized name.

Scripture’s Record — The Procession to Golgotha and who carried the cross.

All four Gospels agree on these points:

- Jesus was led out of the city after being condemned in the Praetorium (the governor’s hall, likely near the Antonia Fortress or Herod’s Palace).

- Simon of Cyrene was compelled to carry the cross (Matthew 27:32; Mark 15:21; Luke 23:26).

- Soldiers escorted him through the streets.

- The destination was called Golgotha, “the Place of a Skull” (John 19:17).

Without question, we know that Jesus walked the road from his place of judgment to Golgotha. However, he was too weakened by scourging to carry the cross. If they tried initially to make Jesus carry the cross, he was unable to do so; otherwise, they would not have pulled Simon of Cyrene from the crowd and forced him to carry it.

Matthew records:

“And as they came out, they found a man of Cyrene, Simon by name; him they compelled to bear his cross” (Matthew 27:32).

Matthew’s words are deliberate—as they came out—meaning after the judgment in Pilate’s hall, Jesus was led away, and the soldiers quickly compelled Simon to carry the cross. Nowhere does Matthew state that Jesus first carried the cross himself. The soldiers, responsible, seized Simon from the crowd and forced him to carry the cross before the procession began its ascent.

Mark’s Account

Mark’s testimony supports this perfectly:

“And they compel one Simon a Cyrenian, who passed by, coming out of the country, the father of Alexander and Rufus, to bear his cross” (Mark 15:21).

Mark writes that Simon was coming out of his country, almost certainly arriving for the Passover feast. The mention of his sons, Alexander and Rufus, suggests that Simon’s family later became known in the early church (see Romans 16:13). Again, no mention is made of Jesus carrying the cross before Simon.

Luke’s Account

Luke’s record adds another key phrase:

“And as they led him away, they laid hold upon one Simon, a Cyrenian, coming out of the country, and on him they laid the cross, that he might bear it after Jesus.” Luke 23:26

As they led him away, here we see the sequence clearly: Jesus was already weakened from scourging, and the cross was immediately placed on Simon of Cyrene. The wording “that he might bear it after Jesus” paints the picture of Simon walking behind the Lord, following in his steps. The burden of wood rested on Simon, but the burden of sin rested on Christ.

As Jesus was led out from the Praetorium to begin the walk toward Golgotha, his appearance was almost beyond recognition. The Roman scourging had been brutal—his back torn open by the flagrum’s metal-tipped cords, his face bruised and swollen from repeated blows. Blood had dried into the woven thorns pressed into his brow.

Isaiah’s prophecy had been fulfilled.

“Just as many were astonished at You—so his visage was marred more than any man, and his form more than the sons of men” (Isaiah 52:14).

Those who saw him must have recoiled in horror.

The Process and Instrument Scourging: The victim was usually severely whipped (scourged) beforehand, often weakening them to the point of collapse or near death.

* To be clear, the patibulum was the horizontal beam, cross member, usually weighing between 75–125 pounds (35–55 kg). This was the portion the condemned person carried to the execution site across their shoulders, after being scourged. The stipes were the vertical posts that were usually fixed permanently at the crucifixion site (like Golgotha).

Carrying the Cross: The condemned was typically forced to drag the horizontal crossbeam (patibulum) to the execution site.

While the full post (stipes) and cross (cross or crux immissa) is most familiar in painting and descriptions, Roman crucifixions used various forms, including: A simple vertical stake (crux simplex); A T-shape (crux commissa); and the familiar cross shape with a crossbeam below the very top of the upright.

One thing is certain: No severely beaten, and very few unbeaten men, could carry an entire vertical thick stake, and the cross piece, up to Golgotha. It would weigh at least 250-275 pounds. It would need to be secured at least two feet into the ground and tall enough and thick enough to support the condemned. Some scholars have suggested that Jesus was crucified upon a single tree trunk because of the use of the word tree in some scripture references. I don’t agree, then again, it was long time ago.

Meanings: Tree ξύλον (xýlon)

Tree (generic), especially when used as wood or timber.

Wooden object — plank, stake, or cross.

In the New Testament:

Used of the cross of Christ, symbolically.

Example: Acts 5:30 — “Jesus, whom you killed by hanging him on a tree (xýlon).”

John’s Account

Only John adds the statement:

“And he bearing his cross went forth into a place called the place of a skull” (John 19:17).

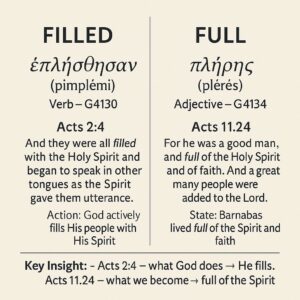

Some interpret this to mean that Jesus carried the cross. Still, the Greek text reveals another understanding: that he went out bearing his cross—that is, carrying the sentence of crucifixion, the divinely appointed burden of death itself. John’s Gospel often conveys truth on a spiritual plane. In this sense, Jesus bore his cross by submitting to the Father’s will and walking beneath the weight of divine purpose. When read alongside the Synoptic Gospels, the full picture emerges:

Jesus never carried the cross to Golgotha himself; all three gospel accounts agree. Was it physically laid upon him, but he was unable to rise and walk? We are not told that. Did the Roman soldiers try to lay the cross upon him? We don’t know. What we do know is that Simon of Cyrene was chosen from among the crowd, and he carried the cross to Golgotha.

Simon was from Cyrene, a Greek-founded city located in North Africa, in what is today eastern Libya, near the modern town of Shahhat.

- It lay on the Mediterranean coast of the region known as Cyrenaica.

- Cyrene was part of the Hellenistic world, colonized by Greeks in the 7th century BC, and later became part of the Roman Empire.

- By the first century AD, it had a large Jewish population — so much so that Jews from Cyrene are specifically mentioned among those present in Jerusalem on the Day of Pentecost (Acts 2:10).

- Many Cyrenian Jews had migrated to Jerusalem and formed their own synagogue. (Acts 6:9).

So Simon of Cyrene was most likely a Jewish pilgrim who had traveled from North Africa to Jerusalem for Passover, along with thousands of others.

The wording in John’s Gospel suggests a spiritual cross rather than a physical one—only Christ could bear: the full weight of humanity’s sin and redemption.

The cross Christ bore was never merely a wooden beam—it was the weight of a fallen world. Simon of Cyrene carried the cross of wood, but only the Son of God could bear the guilt and grief of humanity. What began as a sentence of death ended as a triumph of life. The Lamb of God carried not wood, but sin itself, fulfilling the will of the Father and opening the way for all who would follow him to bear their own cross—not in punishment, but in devotion.

“Surely He has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows… the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all” (Isaiah 53:4–6).

What Simon carried for a brief distance on the road to Golgotha, Christ carried forever—our redemption. The Roman cross was the visible instrument, but the unseen work was the atonement of the world.

Through his suffering, God’s mercy triumphed over judgment, and the curse of sin was broken. The wood Simon carried was heavy, but the burden Christ bore was infinite. Upon His shoulders rested the weight of every sin, every sorrow, every estrangement between God and man. “Surely He has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows,” the prophet declared (Isaiah 53:4).

On the road to Golgotha, that prophecy was fulfilled in full measure. The cross was not simply wood —it was love manifested in suffering, justice satisfied by mercy. And as Simon laid down the beam, Christ bore the greater weight to the very end, until death itself was conquered. From that moment, the cross became not a symbol of shame, but of everlasting victory.

Gratitude,

Anthony Barbera 11-1-25

One Comment

Love this Tony and this morning I just posted before I even read your article a picture of a cross in a hill and posted from Romans 8:11 about the spirit of him who raised Christ from the dead now lives in you! Yay! Victory in Jesus!